Previous Mini-Essays:

Note: This is Part I of a three-part essay on how modern liberation movements lost their moral center—and how rediscovering love and virtue can renew civic life.

Every age carries a hidden story about what it means to be free. Mine began within a movement seeking justice, but slowly drifted from relationship to ideology. What follows is an attempt to uncover how our pursuit of liberation became captivity of another kind—and how rediscovering love may be the way home.

Part One. From Captivity to Clarity: Rediscovering the Soul of Liberation

Part Two. From Clarity to Communion: Beyond the Culture of Separation

Part Three: From Communion to Co-Creation: Birthing the Symbiotic Age

Part I. From Captivity to Clarity: Rediscovering the Soul of Liberation

I wrote this essay for one reason: something real and dangerous is blocking us from coming together.

Our divisions are not only engineered; they also rise from an ancient struggle within the human heart.

After forty years of uniting people across political, class, racial, and faith divides, I’ve seen how captured narratives keep us from working together.

This essay is an invitation to step beyond the tribal scripts that keep us mistrustful and apart. If we hope to build a future rooted in trust and belonging, we must first free ourselves from the stories that keep us from even sitting at the same table.

In his 2025 address at St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Leo XIV urged us to “go and mend the nets”—to rebuild networks of truth and authentic relationships that heal what has been broken:

“Be agents of communion,” he said, “capable of breaking down the logic of division and polarization, of individualism and egocentrism. Center yourselves on Christ, so as to overcome the logic of the world, of fake news, of frivolity, with the beauty and light of Truth.”

That call captures the heart of our moment. Polarization now tears through every sphere of culture—even among those striving for renewal. Division isn’t born only of “the other side”; it grows from our own unexamined assumptions and beliefs once taken for granted as righteous or progressive.

Some of the very ideas that once promised liberation now sow distrust and disunity—in our families, our neighborhoods, and across nations.

To mend the nets begins with looking inward, asking how our inherited ideas—no matter how noble they once seemed—might themselves be feeding the polarization.

That question—how the very ideas that once inspired us can also divide us—has followed me as I finish my book, Birthing the Symbiotic Age, compelling me to dig deep into my own formation: how the movements that shaped my conscience also created my blind spots.

Yet even that story is part of something older and larger—the long drift of Western thought from relationship to abstraction, from the sacred to the merely material, from a living faith to a secular creed. As Pope Leo has reminded us, Jesus entered this world to reveal another way—an end to the ceaseless war of ideas, and the beginning of a new kind of freedom rooted in love itself.

I began to see how that ancient war still wages in subtler forms—even among those devoted to healing and regeneration. While finishing my book, one moment brought that truth into sharp relief.

What I Had to Confront While Finishing My Upcoming Book

A month ago, I read a social media post from a respected colleague who leads bioregional regeneration projects in Europe. His post listed what he saw as “degenerative” aspects of modern society—consumerism, extractive finance, and industrial agriculture. Then I saw it: “the nuclear family.”

That stopped me cold.

Here was a leader I admired, yet his claim revealed something I’ve seen throughout my years as a progressive organizer: we often repeat ideas that sound morally convincing without ever examining their origins—or their consequences.

To most people, the idea that the family is “degenerative” sounds absurd. Yet within some strands of Critical Theory and postmodern thought, it follows an almost flawless internal logic. Both interpret inherited structures—family, faith, and tradition—not as sacred or stabilizing, but as instruments that reproduce hierarchy and control.

Not all progressives—or even all critical theorists—see the family this way, of course, but this framing has quietly shaped much of our cultural vocabulary.

They believe the family reproduces patriarchy and hierarchy; liberation, therefore, means dissolving traditional bonds and replacing them with collectivized systems of care.

Seeing this casual condemnation of the family made me pause—not to judge, but to remember. Because I had once carried similar assumptions. That single phrase about the family exposed how easily good people can inherit harmful ideas—not from malice, but because ideas spread like invisible software, running silently until we examine the code.

That realization led me to a deeper question: Where did this idea come from—and who first declared the family a system of oppression? To answer that, I had to look beyond today’s debates into the hidden genealogy of modern thought—not just about the family, but about liberation itself.

It was the beginning of an inner archaeology—one that unearthed the roots of an entire worldview I had mistaken for truth.

Breaking the Frame – When Our Ideas Start Thinking for Us

I address this issue now as someone who once naturally accepted progressive thought as self-evidently good and true.

I believed that all meaningful change came from the Left, that Western civilization itself was the problem, that business was exploitative, religion regressive, tradition irrelevant. White males were suspect, patriotic people brainwashed, and anyone who didn’t believe systemic revolution was necessary simply “didn’t get it.”

Without realizing it, I lived inside a narrative that divided humanity: the awakened vs. the asleep, the progressive vs. the oppressive, the conscious vs. the conditioned.

I couldn’t see it then, but I had already been captured—not by evidence or truth,

but by ideology.

Because of my dedication to creating a more just world, I mistook political alignment for moral authority. Being on “the right side of history” felt virtuous—even spiritual—but it quietly separated me from the very people I hoped to serve.

I looked down on conservatives, entrepreneurs, and traditional people of faith, dismissing them as obstacles to progress. I had never actually listened to any of these folks; I only carried caricatures of who I was told they were. I could recite statistics on inequality, but not recognize the humanity of my neighbor who saw the world differently.

My activism was fluent in the language of justice but tone-deaf to relationships. What I called compassion often concealed contempt.

As an anti-war activist in 1981, I remember thinking, Why are those 'normies'—the families and small-business owners—going to PTA meetings instead of joining our marches? I had confused activism with wisdom, and moral superiority with moral clarity.

If you want to see how this attitude has surfaced at the highest levels, listen to President Barack Obama: “They [working-class Americans] cling to guns or religion or have antipathy to people who aren’t like them.” And Secretary Hillary Clinton: “You could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables.”

Those sentiments reveal a quiet contempt embedded in the worldview that privileged urban over rural, secular over religious, credentialed expertise over common sense, progressive values over traditional virtues.

This worldview doesn’t unite—it divides.

My liberation began not with a new belief system, but with humility. I recognized that I, too, had been captured when I let unquestioned assumptions do my thinking for me.

By buying the progressive “package,” I surrendered my own agency; I let second-hand narratives quietly decide whom to trust, respect, or love.

Realizing my own version of truth might not be the whole truth forced me to face my shadow. For the first time, I realized I had never actually met the people I claimed to be fighting against. They were straw men, not real human beings.

That’s when I did something radical: I started listening.

In San Diego and later Reno, I began organizing projects that brought unlikely partners together. I sat in church basements, talked with ranchers and veterans, shared coffee with moms who homeschooled their kids, and dads working double shifts.

The illusion cracked: the “ordinary” people I had dismissed were extraordinary—generous, civic-minded, spiritually grounded. They weren’t my enemies; they were my neighbors. They were rooted in values I had unconsciously cast aside—faith, family, loyalty, self-responsibility, and the wisdom born of daily life.

I began visiting churches, mosques, and temples—not as an activist, but as a learner. And in those places, I encountered something my secular activism had never given me: spiritual perspective. I met people who didn’t wave justice slogans but lived justice quietly, every day.

That’s when I wrote in my journal: “We must remove our ideological armor before stepping into the cathedral of community.”

Once I laid that armor down, everything changed. I became curious rather than judgmental, and my heart began to heal from its own division.

My awakening raised a deeper question: if I had been shaped by ideas I never examined, how many others had been, too? To answer that question, I had to follow the thread backward—to uncover where these ideas first took root.

The Genealogy of an Idea – How Liberation Became Ideology

As I traced the lineage of the ideas that shaped my activism, I discovered a coherent arc—from Karl Marx’s critique of the family to Antonio Gramsci’s cultural strategy, Herbert Marcuse’s psychological turn, Paulo Freire’s politicized pedagogy, and Saul Alinsky’s power-first organizing.

Their arc shows how an abstract language of liberation slowly displaced

real-world relationships.

Marx viewed the family as the seedbed of domination; Gramsci shifted the struggle from economics to waging a culture war; Marcuse internalized it into psychology; Freire politicized learning; and Alinsky weaponized organizing.

Seen together, the pattern was unmistakable: the world was recast as a struggle between oppressors and the oppressed, and human relationships were reduced to contests for power. Organizing became less about repairing community and more about wielding power on a human battlefield.

In this inverted moral order, authority no longer flowed from virtue or universal principle but from victory itself—from the ability to prevail rather than the capacity to love or serve.

Here was the hinge for me: this genealogy did not merely critique injustice—it redefined personal relationships as power relationships, an invisible frame that quietly shaped my own activism. I learned to distrust businesses before meeting their owners, to dismiss churches before sitting in their pews, to prefer theory to neighbors. The more I spoke of justice, the less I practiced kinship. I wore judgment like armor and called it wisdom.

These ideas went far beyond challenging unjust systems; they targeted the very foundations of human flourishing—family, faith, place, and covenant—the sacred architecture that binds freedom to civic responsibility.

Once power becomes both the means and the end, transcendence withers, virtue is dismissed as naïve, and relationship is reduced to strategy.

They weren’t dusty academic theories; they were the unseen architects of today’s moral confusion. Ideas once meant to free humanity had quietly untethered us from the sacred order of life itself. For many, critical theory had become the invisible organizing principle, shaping how we love, how we see one another, and even how we understand what it means to be alive.

At the time, I couldn’t see that. I remember reading these authors and how their ideas resonated deeply—the moral clarity, the concern for the exploited, the promise of justice. For someone yearning to make the world fairer, their insights into power, culture, and ideology felt piercingly true.

They gave voice to what I sensed but couldn’t articulate: the hidden power structures shaping society. It took years to realize that their framework, while illuminating, also narrowed my understanding of the human person, leaving little room for grace, relationship, or renewal.

That realization marked a turning point.

How Theory Replaced Reality

I now see I had completely and unconsciously bought into this way of seeing. Let me reiterate, because this is important.

I had come to oppose business as exploitative, the nation as inherently unjust and racist, the West as corrupt, and religion as complicit with empire.

Those convictions didn’t come from my own discernment—they were downloaded assumptions from a worldview I had absorbed without question. The very lens that helped me see oppression also blinded me to relationship—the only thing that can truly liberate us.

To follow the thread, I went back to the sources themselves.

That deeper pattern of life, long obscured by theory, became visible once I traced love back to its source.

What I found shocked me: the roots of ideas I had once called “progressive” were openly hostile to the bonds that hold civilization together.

Marx and Engels wrote in The German Ideology: “The modern family contains in germ not only slavery but also serfdom… it is the prototype of all later forms of exploitation.” For them, the family was the first factory of domination; liberation required dismantling it.

Gramsci echoed the same impulse in Prison Notebooks: “The new order must create its own type of family, its own morality, its own way of feeling and thinking.” He moved the struggle from class to culture, urging a cultural revolution through the capture of schools, media, faith, business, and art.

Marcuse extended this in Eros and Civilization (1955): “The family is the psychological agency of society; its abolition would mean the end of the repressive reality principle itself.”

He saw moral restraint as repression; freedom meant escape from limits rather than the cultivation of wisdom or love.

Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) and Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals (1971) brought the theory into action—education and community organizing became political struggle, embedding suspicion and conflict into the operating system of social change.

Each step carried the same logic: liberation without transcendence, critique without communion, power as salvation. This is how I began to see that our crisis is not merely political or economic—it is metaphysical.

When a relationship is replaced by a theory, reality itself becomes optional.

Once we make meaning through opposition rather than communion, truth itself becomes a construct, and the human person a project to be redesigned. And once reality is negotiable, faith is recast as a naïve fantasy.

Tracing this genealogy left me both humbled and hopeful—humbled by how deeply I had absorbed these ideas, and hopeful that understanding their roots might free us from their spell.

When Liberation Became Religion

What began as a critique of injustice hardened into a program of social re-engineering.

It targeted not only unjust systems but the very foundations of human kinship—family, faith, community, and national identity. Liberation was no longer about healing what was broken; it became about overthrowing the structure of life itself—what I later called “throwing the Baby Jesus out with the bathwater.”

With the Transcendent displaced, a substitute faith emerged: an ideology of liberation in which political theory replaced spiritual wisdom and narrative replaced revelation.

The struggle for justice began as a sacred calling—inspired by the biblical prophets, fulfilled in the Gospel, and carried forward by faith-driven movements from the abolition of slavery to the Civil Rights campaign in the 1960s, each seeking redemption, not revenge.

But over time, its spiritual roots thinned, and it devolved into a new kind of religion—one without forgiveness or grace. Freedom came to mean escape—from tradition, virtue, and responsibility—until belonging itself was seen as bondage.

That is how people raised in loving families can still come to believe the family itself “degenerative.” The enduring truths of early spiritual formation are dismissed as relative—because truth itself has been declared subjective.

This is how liberation became ideology—and, paradoxically, ideology another form of enslavement. The postmodern mind no longer asks, What is good, true, and beautiful? But only who has power —and how do we dismantle them?

In a world where religion no longer binds us, politics becomes the new church, and political identities the warring sects.

After tracing these roots, I saw that what I had mistaken for liberation was really exile—from meaning, true communion, and love itself. Yet that realization opened a doorway: if ideology could estrange us from love, then Love could also lead us home.

The Ancient Blueprint – Love as the Original Protocol

Long before modern ideologies divided the world into competing power systems, a deeper pattern of life was already known—a pattern woven into the fabric of reality itself.

I call this the Ancient Blueprint, and at its center is a truth so simple we overlook it:

Love is not merely an emotion or virtue—it is structure. Love is the ordering principle of life, the architecture of reality, the way creation coheres and grows.

Even beyond Christian theology, this moral structure was recognized across civilizations. C. S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, described an underlying, objectively real moral order—what some Eastern traditions call the Tao, the moral grain of the universe:

“The Chinese speak of … the greatest thing called the Tao. It is the reality beyond all predicates … the Way, the Road. It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time.

It is also the Way which every man should tread in imitation of that cosmic and super cosmic progression.… This conception in all its forms—Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic, Christian, and Oriental alike—meets us in all great civilizations.”

In our Western tradition, the Greeks called this sacred order the Logos—the underlying harmony of reason and being that gives order to the cosmos. Early Christians saw in Christ the embodiment of that Logos—the universal pattern of wisdom and divine love made visible in human life. The Ancient Blueprint is its lived reflection—the social and civic expression of that same ordering principle manifest in relationship and community.

Lewis’s recognition of this universal order affirmed what I had come to see:

The Ancient Blueprint is not sectarian—it is embedded in reality itself.

It is not sentiment—it is ontology, the logic by which being holds together.

Every enduring family, every resilient ecosystem, every spiritually awakened culture has been built on the same foundation: right relationship as the organizing law of life.

Love is not just personal; it is civilizational.

And where love orders reality, virtue gives that order a durable form. The ancients understood that ‘law’ originally meant alignment with reality, not invention by man. Jesus revealed this most clearly when

He said: “You shall love the Lord your God … and love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.”

In other words: Love is the law of life—the principle by which reality remains coherent and whole.

This is where the Ancient Blueprint begins: not in ideology, but in the Transcendent—a divine moral order that precedes mind-generated belief systems. To reject that order is to sever life from its Source, reducing truth to power and persons to objects.

As Jimi Hendrix reportedly observed, “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.”

The result is always the same: people become things to be managed, manipulated, or marketed to.

This is the logic of what I call the Culture of Separation—a world where God is deplatformed, reality is fragmented, and human beings are isolated into economic and political units rather than members of a living whole.

Materialism—the belief that only matter is real—has become the unofficial state religion of the West. It shapes education, governance, media, and even the modern church—where virtue has too often been replaced by virtue signaling.

The progressive movement, which once carried a genuine moral impulse toward justice, ultimately rejected the Transcendent as a source of truth. In trying to free humanity from oppression, it severed culture from objective moral reality.

It fights injustice while ignoring the transcendent truths that make justice possible.

The Living Lineage of Love: A Golden Thread Through History

While empires have come and gone over millennia, the lineage of Love as structure has never disappeared. It runs like a golden thread through history—quietly weaving revival and renewal whenever civilizations lose their way.

It first shone through the revelation of Jesus Christ, whose Sermon on the Mount offered not a philosophy but a way of life grounded in Divine Love — Love God, Love Neighbor, even Love Enemy. The earliest Christian communities took this literally, building a parallel polis of mutual care within the Roman Empire — a “city within a city” bound by faith, trust, and shared resources.

They did not seize temporal power; they embodied a higher and more enduring one: the power of self-giving love.

Two thousand years later, Gandhi rediscovered the same pattern. Reading the Sermon on the Mount, he called it the Law of Love. Through village self-rule (swaraj) and nonviolent resistance, he proved that spiritual truth could transform political reality without hatred or domination.

Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne in Sri Lanka extended this vision through Sarvodaya Shramadana — a movement of thousands of villages that integrated Buddhist virtues, local self-governance, and economic renewal.

Under Communist oppression, Charter 77, and Václav Benda and Václav Havel revived it as the Parallel Polis — a society within a society built on truth, responsibility, and faith in human dignity, grounded in the idea that humans are the image of God.

From Christ’s followers to Gandhi’s and Dr. Ari’s villages to the dissidents of Prague, the same pattern has surfaced again and again: wherever love becomes the organizing principle, renewal begins.

Even nature testifies to this order: in healthy ecosystems, cooperation outperforms competition; diversity sustains strength and can become a greater unity; reciprocity builds resilience. The same relational logic that animates forests also animates faithful communities.

As E. F. Schumacher warned in Small is Beautiful:

“We have recklessly and willfully abandoned our great classical Christian heritage. We have even degraded the very words without which ethical discourse cannot carry on, words like virtue, love, and temperance. … The task of our generation is one of metaphysical reconstruction.”

While writing this book, I began to see that my own relationship with Jesus reframed how I understood both Scripture and history. Far from being reactionary, the biblical story illuminated the same social and moral breakdowns I had spent my life confronting—greed without service, systems without virtue, religion without heart.

Jesus saw the world as it truly is: bound by empire, domination, and fear.

Yet His answer was not to overthrow or reform the existing order but to reveal a new one. He refused the battlefield of power altogether, showing through His life and teaching that love and service form a higher logic capable of transforming the world from within.

The Sermon on the Mount, I came to realize, is not a retreat from public life but a design for it—a blueprint for a parallel order in which love replaces coercion, relationship replaces rivalry, and community becomes the true structure of governance.

Jesus’ “Kingdom of Heaven” was never an escape from the world but the birth of a new one within it—a living Culture of Connection that quietly outlasts every empire.

In that light, what I once saw as purely spiritual now appears as the world’s most enduring civic vision: a polis of communion rather than conquest.

This reconstruction begins wherever people recover transcendence and rebuild civic life around Love as the operating system. It restores harmony between faith and reason, spirit and society, virtue and community. This is not theory; it is a way of life.

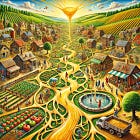

Symbiotic Culture is simply the next living expression of that Ancient Blueprint—linking nature and spirit, inner formation and public action into one coherent whole.

The modern world has forgotten this. We root civilization in ideology, technology, or economics—and then wonder why the result is loneliness, polarization, and decay. Every modern crisis—social, spiritual, economic, ecological—flows from this deeper loss: the abandonment of Love’s architecture. The collapse is not political or technological but spiritual—a loss of meaning, true connection, and coherence.

It is the predictable outcome of building a world without God, a society without transcendence, a culture without a shared moral center.

But the Blueprint has not abandoned us. It waits to be re-embodied in families, neighborhoods, whole communities, and cultures once again aligned with reality.

Love’s protocol is ever-present; what remains is to re-platform it.

Each re-embodiment—Jesus, Gandhi, Ari, the Czech dissidents—reveals the same pattern surfacing whenever empire forgets its soul. Each calls us back to the Transcendent ground of truth, goodness, and beauty. And each begins with communities that choose Love as their civic protocol.

This is why I say Symbiotic Culture is not new. It is simply the next chapter of an ancient continuity. It lives the same progression: inner transformation (Metanoia) → relational healing → local cooperation → federated networks → parallel society. It does not begin with politics but with people. It does not enforce belonging from the top down but cultivates it through trust at the neighbor-to-neighbor level. It does not seize power; it grows moral authority through lived virtue.

The Ancient Blueprint reveals a simple reality:

• Love is the foundational structure

• Virtue is operational infrastructure

• Relationship is the architecture of governance

• Weaving community is the public expression of Love

And this is why our work must be both spiritual and civic—a return to the Source that restores coherence from within and a rebuilding of culture in the shape of Love from below. This is how civilizations are renewed: not through ideology but through lived love that brings the Transcendent into daily life.

The question before us is civilizational: Will we continue in the Culture of Separation that divides and dehumanizes, or will we recover the Ancient Blueprint and rebuild a world ordered by Love—a Culture of Connection?

Choosing love truly disrupts the status quo, because it lifts us off the battlefield that social-engineering movements—and their opponents—perpetuate.

Every age that rediscovers love’s primacy threatens empires built on fear, pride, and control. Relationship decentralizes power because it makes every person sacred, every bond meaningful, every community self-organizing. Systems of domination—political, economic, ideological—always try to domesticate love, turning it into sentiment rather than structure.

But true Love cannot be managed. It exposes false gods and unseats surrogate powers. It dissolves hierarchies that feed on separation and awakens conscience beyond coercion.

To remember that Love is law is to remember that no ideology, however righteous it claims to be, can own the human soul.

Yet even with this lineage to guide us, we still forget. The Blueprint survives, but our memory of it fades. I know—I forgot too. I had to relearn, through experience, how easily unspoken assumptions can hijack good intentions. What I’ve witnessed in my own life—and in the lives of people I love—shows just how many cultural landmines now keep us divided, trapped in competing camps instead of working together for the common good.

The forgetting was not only mine; it is civilizational. Every generation inherits both the wisdom that holds life together and the amnesia that tears it apart. I realized that the same forces that once recoded my own ideals now shape whole cultures—teaching us to separate before we relate, to manage before we love. Part Two begins where that realization led me: into the everyday work of remembering together.

Part One traced the ideas that fractured love’s design. Next, in Part Two reveals how we can mend it—beginning in our families, friendships, neighborhoods, and local networks, then extending outward to the rebuilding of whole cities and cultures.

Through personal stories, unlikely encounters, and lessons from civic renewal, we’ll see how Love still works—quietly, powerfully, reweaving the fabric of relationship and laying the groundwork for a parallel society, economy, and culture wherever people dare to live it.

Part One. From Captivity to Clarity: Rediscovering the Soul of Liberation

Part Two. From Clarity to Communion: Beyond the Culture of Separation

Part Three: From Communion to Co-Creation: Birthing the Symbiotic Age

To learn more about the Book click HERE, or purchase below:

Tik tok. Instagram etc speaks to our animal fast brain with emotional candy. Deliberative democracy engages our slow brain allowing us to see others and feel others through deep conversation.

people come out of public deliberations saying “there was love in that room“.

I think the solution to nearly all our complex problems is to build processes in which love can flourish through civic deliberation.

see braverangels.org and deliberationgateway.org

“…right relationship as the organizing law of life.” What a truly great post. Thank you.